What comes to mind when you hear “cruel and unusual punishment”? I think of a villian in a dank lair who has James Bond strapped down. Electric shocks applied via clamps, slicing off ears, shards of glass under fingernails. Skinning alive, dripping acid through a cut in the scalp. Breaking small bones one… by… one…

I was puzzled to learn that jurisdictions within in the Ninth Circuit can’t clear homeless encampments without first offering every homeless person shelter because doing so would be considered “cruel and unusual punishment.” Really? Writing someone a ticket or jailing them for a short time? That sounds cruelty-free and common.

The Supreme Court recently decided to hear an appeal to Grants Pass v. Johnson, a case which prevents cities from enforcing laws against camping on public property. The legal theory is that such laws violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. But how? I decided to take a look at a few cases which set precedent on the interpretation of Eighth Amendment to figure out how writing tickets for camping on city sidewalks came to be considered “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Here’s the full text of the Eighth Amendment:

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

So, what does “cruel and unusual punishments” mean, exactly? The Eighth Amendment was copied almost verbatim from Section 10 of the English Declaration of Rights of 1689, which, in turn was motivated by punishment methods used on the perpetrators of the Monmouth Rebellion (which included drawing and quartering, burning of women felons, beheading, disemboweling) or the sentence handed down to Protestant cleric Titus Oates, a perjurer who was sentenced to be "stript of [his] Canonical Habits," to stand in the pillory, to be whipped, and to life imprisonment.

Indeed, there’s ample evidence from historical documents that those voting at state ratifying conventions to accept or reject the constitution understood the Eighth Amendment to apply to methods of punishment, not what could be punished.

Punishing a status

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of “cruel and unusual punishments” expanded in its landmark decision Robinson v. California (1962) to include criminalizing a status. In that case, a Los Angeles police officer arrested Robinson because they noticed that he had track marks on his arm and he admitted to past use of narcotics. Robinson was sentenced to 90 days in prison for being addicted to narcotics — a crime under California law at the time. The SCOTUS ruled that it was unconstitutional to punish someone for a state of being or status rather than a criminal act.

This changed the meaning of the “cruel and unusual” clause. Before, it was commonly understood to prohibit types of punishment assigned after conviction. Robinson’s punishment itself (a short prison sentence) was clearly neither cruel nor unusual in the common sense. In the Robinson decision, the SCOTUS expanded the Eighth Amendment to prohibit criminalizing status, arguing that because a person’s status is beyond their control, any punishment (and therefore, any criminal enforcement) would be “cruel and unusual.”

Punishing acts that follow from a status

You can see where this is going. If it’s unconstitutional to punish someone for being homeless, can you punish them for acts that are unavoidable when they are homeless? Can you enforce laws against camping on sidewalks or in parks? What about laws against public urination or defecation? If someone can’t afford food, does it become unconstitutional to enforce laws against stealing food? If so, can an indigent person legally dine and dash?

The Ninth Circuit answered some of these questions when they ruled on Martin v. Boise. They found that the Eighth Amendment also makes it unconstitutional to criminalize sleeping in public when there is no shelter space available:

That is, as long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors, on public property, on the false premise they had a choice in the matter.

The ruling claims that it does not “dictate to the City that it must provide sufficient shelter for the homeless, or allow anyone who wishes to sit, lie, or sleep on the streets . . . at any time and at any place.” However, it effectively does this, as it prevents the city from enforcing laws against public camping when homelessness is “involuntary” — that is, when the city doesn’t provide shelter to the homeless. It is theoretically acceptable for cities to implement “time and place” restrictions on camping, but the cost of daily enforcement may be prohibitive and activist groups have sued to ban these types of restrictions as well.

Dissent

Martin v. Boise was decided by a panel of three judges, and a petition for an en banc rehearing (which would allow 11 judges to rehear the case) did not win sufficient votes to move forward. In his dissent to the denial of this rehearing, Judge M. Smith cited several cases which contradicted his own court’s findings:

Tobe v. Santa Ana (1995) The California Supreme Court rejected an Eighth Amendment claim against a law that banned city camping — despite not having enough shelter beds for all.

Manning v. Caldwell (2018) The Fourth Circuit found that a law banning alcohol possession by “habitual drunkards” did not violate the Eighth amendment rights of homeless alcoholics because it prohibits the act of possession, not the state of being a habitual drunkard.

Joel v. City of Orlando (2000) The Eleventh Circuit rejected an Eighth Amendment challenge to a law against sleeping on public property because it “targets conduct, and does not provide criminal punishment based on a person’s status.”

He predicted the conditions that would become common in Ninth Circuit cities:

“Under the panel’s decision, local governments are forbidden from enforcing laws restricting public sleeping and camping unless they provide shelter for every homeless individual within their jurisdictions. Moreover, the panel’s reasoning will soon prevent local governments from enforcing a host of other public health and safety laws, such as those prohibiting public defecation and urination.

“They must either undertake an overwhelming financial responsibility to provide housing for or count the number of homeless individuals within their jurisdiction every night, or abandon enforcement of a host of laws regulating public health and safety. The Constitution has no such requirement.”

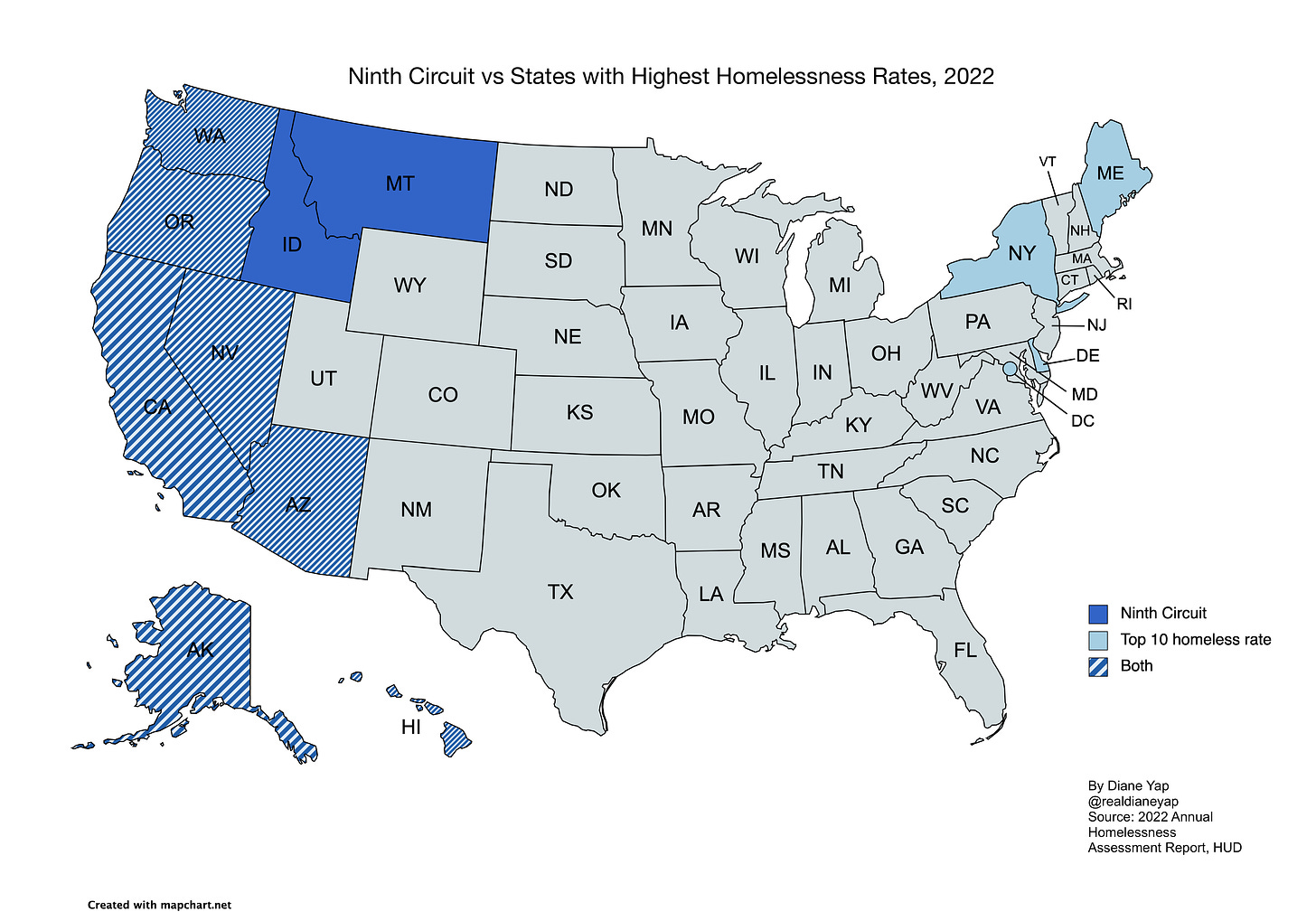

Indeed, seven of the nine states within the Ninth Circuit are now among the states with the top ten highest rates of homelessness as of 2022. While this is not definitive proof that the Martin v. Boise decision caused the homelessness problem, it is easy to see why a state that must either allow public camping or provide free housing might be more popular as a destination for the homeless.

Judge Smith also noted that the verdict crosses the line from interpreting the law to forcing the hand of policy-makers: “By creating new constitutional rights out of whole cloth, my well-meaning, but unelected, colleagues improperly inject themselves into the role of public policymaking.”

In a separate dissent, Judge Bennett explains the problem with ruling that criminalizing behaviors violates the Eighth Amendment:

“In so holding, the panel allows challenges asserting this prohibition to be brought in advance of any conviction. That holding, however, has nothing to do with the punishment that the City of Boise imposes for those offenses, and thus nothing to do with the text and tradition of the Eighth Amendment.”

In fact, he goes further and notes that a plurality of the Supreme Court “has rejected the notion that the Eighth Amendment’s protection from cruel and unusual punishment extends to the type of offense for which a sentence is imposed.”

What will SCOTUS do?

I believe the SCOTUS will overturn Grant’s Pass v. Johnson and thus also nullify Martin v. Boise. Here’s why:

This would resolve the circuit court split: the Fourth and Eleventh circuits both found that the Eighth Amendment did not apply to similar cases as noted above in Judge M. Smith’s dissent.

There are five current Supreme Court justices who are originalists (or who appear to lean that way): Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Coney Barrett and Kavanaugh. The originalist reading of “cruel and unusual punishment” is more similar to my layman’s imagining at the very top than to the Ninth Circuit’s interpretation.

Based on data from years 1986-2018, the SCOTUS has historically granted cert to more cases from the Ninth Circuit than any other circuit court: over 24% of all the cases it agrees to hear. The SCOTUS reverses nearly 76% of Ninth Circuit decisions it agrees to hear — the highest rate of any circuit court.

A reversal will be good news for Ninth Circuit states struggling with homelessness. Enforcement may not solve homelessness, but local governments are unable to compel different behavior without enforcement. The fallout from lack of enforcement is on display daily in cities throughout the Ninth Circuit. We need all the help we can get.

Outstanding article, Diane

Good essay Diane.