Watch a school board discussion on the academic achievement gap and you will hear members of black advocacy groups say “we just need more resources!” They repeatedly claim that other schools have high levels of academic proficiency because they receive “more resources” or are “hoarding resources.” But is this true?

How money allocated to SFUSD schools

This post was inspired in part by an article in the SF Standard suggesting the use of “local norms” (reserving seats at Lowell for the top students at each SFUSD middle school). In it, Virginia Marshall (education chair of the SFNAACP) implied that Lowell is out of reach for some students because they grew up in housing projects or attend “underfunded elementary and middle schools.” That is a mischaracterization of how schools are funded within SFUSD.

SFUSD allocates funds using the Weighted Student Formula, which gives sites more funding per pupil for each student who is a foster child, homeless, living in public housing, an English language learner, or who qualifies for free or reduced lunch or special education. There’s even a “concentration bonus” — schools receive extra funding if 55% or more of its students fall into one or more of the categories above. The following analyses are based on this SFUSD budget spreadsheet maintained by Tim Tahoe and CAASPP test results from EdData.

Of the 10 best funded general education elementary, middle and k-8 schools:

7 of 10 are predominantly black + Hispanic (>50% of the student body)

Considering these 7, the average pass rate on the CAASPP is just 18.43%

The three schools which have more Asian + white students than black + Hispanic students had a much higher average pass rate of 53.55%.

All but 1 of these are “Title 1” schools (the percent of low-income students at the school exceeds their proportion in SFUSD)

Of the 10 worst funded elementary, middle and k-8 schools, we find the opposite:

Relatively high average pass rate of 73.79%

9 are predominantly Asian + white (on average, about 65% of the student body).

The 1 outlier with less than 50% Asian + white students also had a much lower pass rate of 60.20%

None of these are Title 1 schools.

So, to recap, if anyone is going to “underfunded” schools within SFUSD, it’s Asian and white students. It’s students who are not low income or attending schools with a disproportionate number of low income students. Not a single one of the 10 worst-funded SFUSD elementary or middle schools is predominantly black + Hispanic. Not one. And yet, I doubt Virginia Marshall is concerned that these underfunded schools are putting Lowell out of reach for Asian and white students!

But SFUSD is just one school district.

What does the relationship between school funding, race and performance look like at the state level?

California’s school spending is above the national average, and black students receive ~$2500 more per year on average than white students, and ~$2000 more per year than Asian students:

If funding is the primary driver of results then in California, black students should enjoy the highest achievement levels, and white students, the lowest. Here’s the reality:

Despite enjoying the most funding on average, black students have the lowest rates of academic proficiency. While Asian students, who receive less funding on average than students of all groups other than white, performed the best. To recap, black students are not given less funding on average than other students: in fact, they’re the best funded of any racial group in California.

You may have read a national statistic that the districts with the most white students receive an average of $2700 more per pupil districts with the most non-white students. This is based on an analysis that directly compares school districts while only normalizing for teacher salary. Clearly there are differences in local operating costs not reflected in teacher salary alone, and none of these are accounted for. A more accurate picture arises when examining funding by race within school districts, as done above for SFUSD. A 2017 paper on intra-district funding by race reveals “poor and minority students on average receive 1 to 2 percent more resources than nonpoor and white students in the same district.”

But will giving schools more money improve academic performance?

The short answer is no. A couple of illustrative examples followed by the general case:

Kansas City

Following a 1985 court decision finding that Kansas City schools were illegally segregated, a judge ordered the district and state to spend two billion dollars over 12 years to integrate schools and close the black-white achievement gap. This amounted to more per pupil funding than any of the 280 major school districts in the country. The following excerpt from a Cato Institute report gives an idea of how the money was spent:

With that money, the district built 15 new schools and renovated 54 others. Included were nearly five dozen magnet schools, which concentrated on such things as computer science, foreign languages, environmental science, and classical Greek athletics. Those schools featured such amenities as an Olympic-sized swimming pool with an underwater viewing room; a robotics lab; professional quality recording, television, and animation studios; theaters; a planetarium; an arboretum, a zoo, and a 25-acre wildlife sanctuary; a two-floor library, art gallery, and film studio; a mock court with a judge's chamber and jury deliberation room; and a model United Nations with simultaneous translation capability.

For students in the classical Greek athletic program, there were weight rooms, racquetball courts, and a six-lane indoor running track better than those found in many colleges. The high school fencing team, coached by the former Soviet Olympic fencing coach, took field trips to Senegal and Mexico. The ratio of students to instructional staff was 12 or 13 to 1, the lowest of any major school district in the country. There was $25,000 worth of beads, blocks, cubes, 19 weights, balls, flags, and other manipulatives in every Montessori-style elementary school classroom. Younger children took midday naps listening to everything from chamber music to "Songs of the Humpback Whale." For working parents the district provided all-day kindergarten for youngsters and before- and after-school programs for older students.

The result? Despite the expense, there was no improvement in academic achievement, the black-white achievement gap didn’t budge, and the district became more segregated.

Willie Brown Middle School, San Francisco

With the Kansas City result as a cautionary tale, one would think San Francisco could have avoided the same “more resources” wishful thinking when opening Willie Brown Middle School in 2015 at the cost of $54 million. But the story is startlingly similar. WBMS was intended to be a STEM academy featuring robotics labs, organic urban farming gardens, solar panels. Every student would receive a chromebook, free breakfast and lunch, medical and dental care. It is, to date, the only middle school in SFUSD equipped with a science lab.

But chaos reigned immediately:

“The first day of school there were, like, multiple incidents of physical violence.” After just a month, Principal Hobson quit, and an interim took charge. In mid-October, less than two months into the first school year, a third principal came on board. According to a local newspaper, in these first few months, six other faculty members resigned… In a school survey, only 16 percent of the Brown staff described the campus as safe. Parents began to pull their kids out.

Some of the problems could be fairly attributed to poor planning and disorganization around opening, but where does WBMS stand today, nearly a decade later?

The proficiency chart above shows how WBMS compares to other district schools and to middle schools state-wide and appears to be based on 2018-2019 data. The latest SFUSD data from 2022-2023 show English proficiency to be ~34% and math proficiency ~19%:

Still, these numbers are dwarfed by both district and state averages.

General case — nationwide statistics

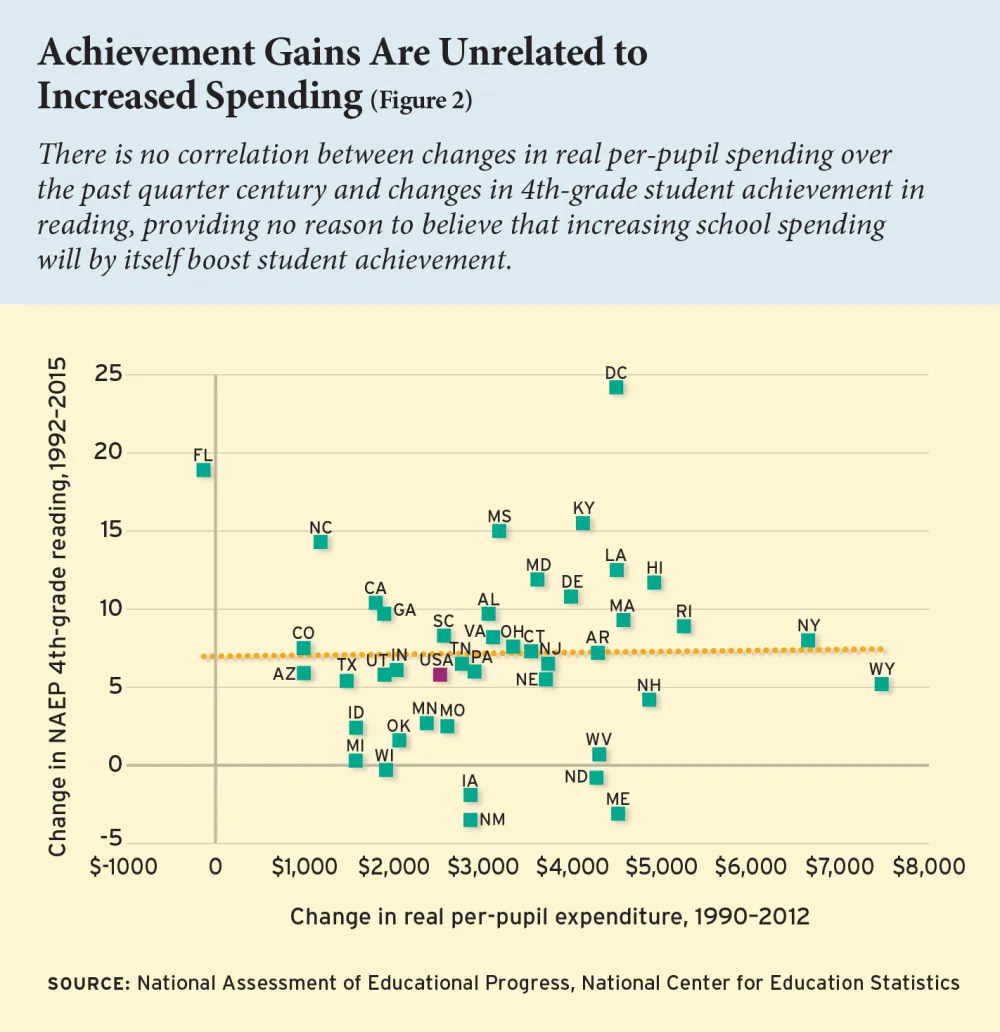

In general, there is nearly zero correlation between school funding increases and academic performance of students as shown in Stanford economist Eric Hanushek’s analysis:

In the same piece, Hanushek reports that though school funding has more than quadrupled in inflation-adjusted numbers between 1955 and 2010, with average class size decreasing from 27 to 16, performance in reading and math (as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress) has remained flat over the same time period.

In a more recent article, Hanushek and his co-authors analyzed studies from the past two decades that are characterized by quasi-experiemental changes in funding. Each case involved “a change in resources that is not correlated with other factors that affect student outcomes” (such as a court order or budget cuts resulting from the 2008 recession) and “the availability of a control group that can indicate what would happen in the absence of the added resources.” Fewer than 20 studies fit these criteria. This time, they found that school spending is positively correlated with academic outcomes, but results varied widely: “estimates for test scores range from a reduction in achievement of −0.24 SD (not statistically significant) to +0.54 SD (statistically significant).” Unfortunately, they were unable to pinpoint which expenditures maximized educational attainment or performance.

The takeaways

Nonwhite students do not receive less school funding than white students. On average, they receive more.

Funding levels are not correlated with academic outcomes. For example, in California, black students receive the most funding on average and achieve the worst outcomes.

A quadrupling in (inflation-adjusted) average school funding over 5 decades throughout the country did not result in improved academic outcomes.

Capital improvements (e.g. new school buildings, swimming pools and robotics labs), reductions in class sizes, increases in teacher salaries, “wraparound services” like free meals and health care, did not result in improved academic outcomes.

My hope in writing this is that the constant refrain “we just need more resources” can be put to rest. The goal should be to identify the most effective ways to improve academic outcomes given the resources already allocated. Why should taxpayers give more money to school administrators who apparently have no idea what will actually improve academic performance?

Diane Yap is probably my favorite human being right now. I love this broad!

In 2008, 9 and 10 the Obama DOE dumped truckloads of ARRA money into schools, spending 50 plus million on the “School Improvement Program” at nine low performing SFUSD schools while spending billions on the same program across the country. The principal at one of the schools and a long time school board member said he didn’t know what to do with all the money. At that time I did a deep dive into its implementation and results over a period of years. It was very much akin to what Diane described about Kansas. The end result was about a third of schools did marginally not significantly better, third the same and a third worse than their baseline achievement scores per California’s standardized testing. Computers were disappearing and private education contractors were getting rich. After it was all over there were many national articles written about how the SIP (School Improvement Program) was a total bust. Diane may have been at Lowell at this time and probably didn’t follow this debacle at that point in her young life.